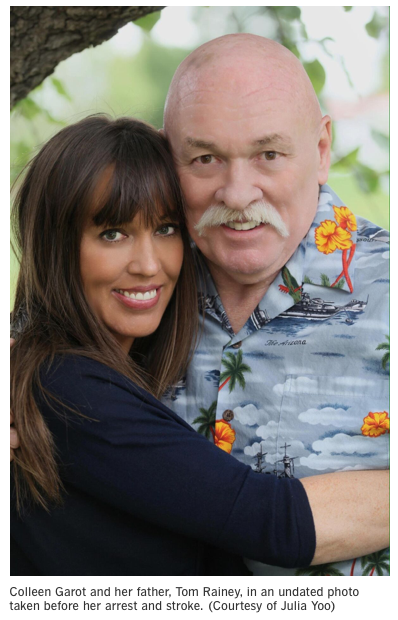

Colleen Garot, a mother of two, now requires around-the-clock care at a skilled nursing facility.

The county of San Diego has agreed to pay $9.5 million to a woman who suffered a debilitating stroke in the Las Colinas jail in Santee five years ago.

The county of San Diego has agreed to pay $9.5 million to a woman who suffered a debilitating stroke in the Las Colinas jail in Santee five years ago.

The lawsuit that led to the settlement argues that when Colleen Garot was arrested, deputies and later jail medical staff should have recognized signs of head trauma that needed immediate medical attention.

Instead, she was booked into jail, where, over a three-day period, the swelling, bruising and neurological symptoms she had had since deputies first encountered her worsened until she suffered a stroke.

“As the result of the repeated denial of medical care, Ms. Garot spent her time in Defendants’ custody in unnecessary and excruciating pain, suffering and agony,” the lawsuit says.

Garot, a mother of two, now requires around-the-clock care at a skilled nursing facility.

She uses a wheelchair, and her ability to move her arms and legs is limited. In video clips her lawyers shared with the Union-Tribune, she struggles to communicate verbally or recall basic details about her life.

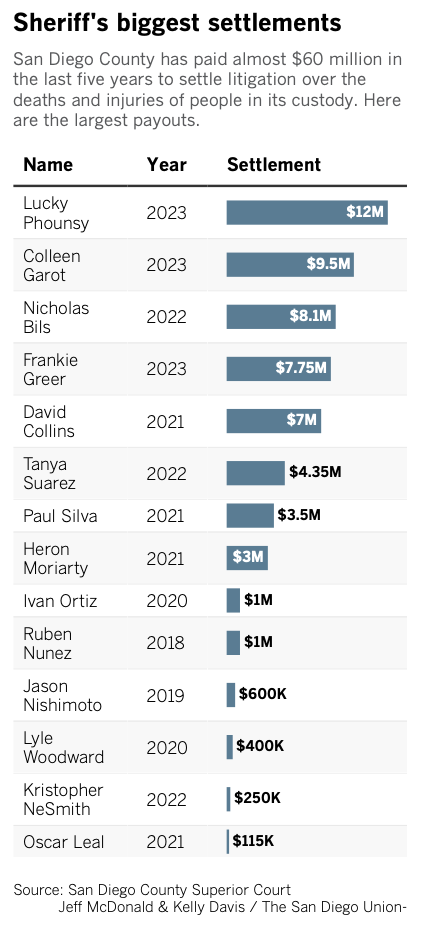

Garot’s payout brings to nearly $60 million the amount the county has paid over the last five years to people who have died or been seriously injured in sheriff’s custody. Hers is the second-largest payout in that time.

The largest settlement, $12 million, was paid earlier this year to the family of Lucky Phounsy, who died after being beaten, repeatedly tasered and hogtied during a struggle with sheriff’s deputies.

A Sheriff’s Department spokesperson said he could not comment on Garot’s case specifically, but said that the department “strives to provide the best medical care to all persons who encounter our deputies.

“Whether in custody or in public, anytime deputies recognize that there is a need for medical care, they are to request an emergency medical response or transport those in need to a local hospital for care,” Lt. David LaDieu wrote in an emailed statement.

Garot was 45 when she was arrested at her home in Encinitas, where sheriff’s deputies had gone to evict her the morning of April 13, 2018. Once there, they discovered she had an outstanding warrant tied to a 2017 DUI.

Severe bruising around Garot’s left eye is visible on body camera footage. The condition, known as “raccoon eye,” should have been recognized as a sign of head trauma, said Garot’s attorney, Eugene Iredale.

In Garot’s case, the bruising was caused by a subdural hematoma, hospital records would later reveal — internal bleeding that was putting pressure on her brain. Smaller bruises and abrasions dotted her forehead and arms, video footage shows.

Garot had trouble walking to the patrol car and told deputies she had “a very weird affliction” and was “in neurological hell.”

Her lawsuit argues that the deputies who arrested her had been trained to recognize raccoon eye as a symptom of head trauma and should have immediately brought her to a hospital.

What caused Garot’s initial injuries remains unknown, despite an investigation later carried out by the sheriff’s department, said Steven Hoffman, another one of Garot’s attorneys.

Due to the extent of her brain injury, Garot herself does not remember what happened.

“The deputies did an investigation and interviewed several people, but we never found out how she incurred the original injuries,” Hoffman said.

“She was shaking all the time,” one woman who had been incarcerated with Garot told investigators. She said Garot did not realize where she was, repeatedly tried to open doors and wondered where she had left her purse.

“She looked pretty beat up,” her face “black and blue all over,” another woman said.

Shortly after her arrest, Garot was moved from the Vista Detention Facility to the Las Colinas women’s jail in Santee. Records from medical encounters at both jails note the bruising and swelling to Garot’s left eye and that she had a “chronic unsteady gait” and body tremors.

Yet no one administered the basic neurological assessment that her lawyers say would have revealed Garot was suffering from a brain injury.

Hoffman said it appeared few nurses knew how to perform such an exam, which asks about things like limb movement, speech and level of consciousness.

“During the depositions, I asked most of the nurses … about the sheriff’s policies and procedures regarding neurological assessment. Most could not tell me exactly how to perform one per policy,” Hoffman said.

On April 14, Garot fell from a top bunk bed in her two-person cell at the Vista jail.

According to jail medical records, she told staff she had briefly lost consciousness, but she was treated only with an ice pack for a bump on the back of her head — which turned out to be a skull fracture.

After being transferred to Las Colinas, Garot was placed in the general population, where another woman hit her in the head because she would not stop talking to herself.

By April 15, records showed Garot had become “agitated and uncooperative” and had made “repeated, nonsensical statements” to jail staff.

By April 15, records showed Garot had become “agitated and uncooperative” and had made “repeated, nonsensical statements” to jail staff.

That prompted them to move her to a safety cell — a tiny, bare cell used to monitor people who are suicidal.

Closed-circuit video shows Garot stumbling around the cell, naked, talking to herself and attempting to climb the wall. A psychologist who assessed her noted that she was hallucinating.

A physician, Dr. Friederike Von Lintig, came to the cell for a scheduled check and conducted a patient assessment through the cell door’s window and food flap, records show. Sheriff’s department policy barred her from entering to conduct a medical exam.

She concluded that Garot was suffering from a psychotic episode but later added in a deposition that a head injury could have caused her behavior.

Von Lintig is currently charged with involuntary manslaughter in the death of 24-year-old Elisa Serna at the same jail in 2019.

Twenty-four hours after being placed in the safety cell, video footage shows Garot falling to the floor and having a seizure.

Although safety cell placement requires visual checks every 15 minutes, nearly two hours passed before a deputy opened the cell door and summoned paramedics.

By the time of her seizure, the blood from her subdural hematoma had accumulated enough to displace Garot’s brain, pushing it over to the right side and causing a stroke.

Dr. Homer Venters, a physician and jail health care expert hired by Garot’s attorneys, described what happened to her as a “catastrophic medical emergency [that] was both preventable and the direct result of gross medical negligence in the care she received while incarcerated in the San Diego jail system.”

Garot was taken to Sharp Memorial hospital where, in addition to the subdural hematoma, she was diagnosed with a skull fracture and respiratory failure, among other injuries.

Iredale said that intervention at any point before Garot’s seizure could have prevented the brain damage she ultimately suffered.

“This was so obvious,” he said, “and involved not any esoteric application of medical policies or the need for complicated and nuanced medical judgment. It just required an eye, common sense and a heart. And apparently that equipment is optional in respect to many employees and contract employees at the county jail.”

Garot’s attorneys said part of the settlement money will allow her to be transferred to a facility that focuses on neurological rehabilitation, offering the possibility that she may regain the use of her hands and someday be able to feed herself.

The settlement is only between the county and Garot. Two other parties — Coastal Hospitalist Medical Associates and Liberty Healthcare, the contractors that employed two jail doctors, a nurse practitioner and a psychologist — are still litigating the case.